On Saturday, 11th June 2023, as part of Æthelfest 2023, I gave a talk at Tamworth Castle. Here is the transcript from that talk:

Lady Æthelflæd - Warrior? Queen?

[I began by thanking everyone for coming, and also expressed gratitude to Tamworth Borough Council and the organisers of Æthelfest for inviting to talk about one of my favourite Mercian women, who has a special place in my heart particularly as my novel about her really launched my writing career.]

To me, she has always been something of an enigma - a female ruler in a time when men were pretty much always in charge of kingdoms, a woman about whom so much has been said and written but about whom we actually know very little. A woman worthy of mention, yet hardly mentioned in the contemporary records.

So, was she a warrior woman? Was she a queen?

Perhaps we should start with what we DO know about her life, or rather, what we can piece together. And I must say at the outset, it really isn’t much. She is barely mentioned in the main stock of the annals known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (ASC), though we do have a preserved portion of a document known as the Mercian Register, which records her activities from 902-918. It is assumed that she was born around 870, but we don’t know. It is possible that she spent some of her childhood away from the court of the West Saxons, where her father, Alfred, was king. If so, Mercia would have been the obvious place because her mother was a Mercian, the daughter of a high-ranking nobleman, a tribal leader, and her paternal aunt was married to the Mercian king. We know that she was the eldest of Alfred’s children, because a Welsh monk, Asser, commissioned to write a biography of Alfred, tells us so. Asser spent time in Alfred’s court, so we must assume he knew the family well, although, oddly, he never tells us the name of Alfred’s wife! (And this strikes at the heart of our problems - the chroniclers didn’t often give us much in the way of detail about even the most high-ranking women of the time.)

In 886, (again, we’re not sure, but we assume it was in this year) Æthelflæd was married to the ealdorman of Mercia, seemingly as a diplomatic bride. This man was Æthelred. He’d helped Alfred take back London from the vikings and it appears that the marriage was the seal on the alliance between Wessex and Mercia.

Æthelred was a tried and tested warrior - We have to assume this because he was obviously accepted as the leader of the Mercians once they’d effectively run out of kings, and he is named as being the man to whom Alfred entrusted London once it had been regained - and it’s safe to assume that he was older than his wife by some years.

He was named in the sources, fighting alongside Alfred against the encroaching Danes and, later on, with Alfred’s eldest son, Edward, too.

The campaign against the Viking invaders is quite long and complicated, but I just want to highlight a couple of incidents. One is when Alfred came to an agreement with a Viking named Hasteinn and where Hasteinn gave oaths and hostages, and his sons were baptized with the sponsorship of Alfred and the ealdorman Æthelred. Another was when Alfred’s son, Edward, besieged the enemy and ‘Earl Æthelred lent his aid to the prince [Edward].’ The three leaders were clearly working in concert together and are named as doing so in the annals.

And then, around 902, Æthelred's name stops being mentioned. In 906, we’re told, Edward was forced to make peace, temporarily, with the Vikings ‘from necessity’. (Alfred had died by this point and there’s no mention of Æthelred, so Edward appears to be alone now.) In a few short years the English resistance had withered from a triumvirate to Edward working, seemingly, on his own. Gone are the comments along the lines of ‘with the aid of Æthelred, earl of the Mercians’ and then in 907, we’re told that Chester, in Mercia, was restored, i.e. wrested back from Viking control, but we’re not told by whom. Æthelred seems to have disappeared.

When we look at sources from outside Wessex and Mercia, specifically the Irish annals, we can see that he was ill, and here we are told that Æthelred, whom they call the king of the Saxons, was on the point of death yet still advising as to the best course of action.

The Irish fragmentary annals known as the Three Fragments records that when Chester was overrun those inside the city sent messengers to the King of the Saxons i.e. Æthelred, who was in a disease, and on the point of death at that time, to ask his advice, and the advice of his queen. The advice which he gave was, to give [them] battle near the city outside, and to keep the gate of the city wide open, and to select a body of knights, and have them hidden on the inside ; and if the people of the city should not be triumphant in the battle, to fly back into the city, as if in defeat, and when the greater number of the forces attacking came inside, those there should close the gate and attack. There was, apparently, a ‘red slaughter’’ but still it wasn’t over, and we are told that the king, who was on the point of death, and the queen sent ambassadors to the Gaeidhil (Irish) and the message begins "Life and health from the King of the Saxons, who is in disease, and from his Queen, who has sway over all the Saxons” and then it goes on to request aid.

The annal goes on to say that many were killed with large rocks and beams hurled down upon their heads. The Saxons, apparently, also boiled up all the beer and water in the town to throw down on the invaders, and then threw beehives down on them, at which point they left. [Well you would, wouldn't you?]

Now in the course of telling this detailed episode, the Irish annalists tell us twice that Æthelred is ill. Neither the ASC nor even the Mercian Register records Æthelred's illness, but when Edward gathered West Saxon and Mercian forces and went harrying into Northumbria, there is no mention of Æthelred. When, presumably in retaliation, the Northumbrians broke peace, and ravaged Mercia, at the ensuing battle at Tettenhall, Æthelred is not mentioned.

So it seems safe to say that he was ill for some years before his death, but still somehow able to rule.

For corroboration, we can look to that annal which is known as the Mercian Register, compiled in Mercia, and inserted, as I said earlier, into the common stock of the ASC. It does show Æthelflæd engaged in rather ‘queenly’ behaviour whilst her husband was still alive. For it tells us that it was she who built a burh, a fortified town, in 910. So, she’s clearly acting for him.

This, of course, changed with his death in 911. What is odd, and almost unprecedented, is that Æthelflæd then became the leader of the Mercians. From this point until her death in 918, here in Tamworth, she worked in tandem with her brother Edward, (although Edward took over control of London and Oxford, he left his sister to rule the rest of free Mercia), pushing back the Danes and carrying out a concerted and strategic campaign of burh-building with Edward building five fortresses and Æthelflæd building nine and both had the enemy submitting to them. The campaigns appear to have been very coordinated.

In the middle of all this frenetic activity she sent an army into Brycheiniog (to Llangorse Lake) in Wales. The Mercian Register tells us that this was to avenge the death of an abbot but we have no further detail. The following year she took the borough of Derby and in 918 The Three Fragments says that she directed a battle against the Dublin-Norse, ordering her troops to cut down the trees where the ‘pagans’ were hiding. Thus we are led to believe that as well as partnering her brother in an extensive and well co-ordinated attack on the Danes, she was conducting her own campaign against the Norse. I have to say I’m a bit sceptical about this one, which would have us believe she she nipped up to Corbridge in Northumbria and back down again in very quick time. [It also says that she entered into an alliance with Alba and Strathclyde - this came up in the Q&A afterwards]

But in Mercia, between them brother and sister regained control of crucial areas: the five boroughs of Lincoln, Stamford, Nottingham, Derby and Leicester.

In the year of her death, she was approached by the Danish leaders of York, who seem to have submitted to her in return for her protection although she died before being able to assist.

She was also an effective administrator, seemingly. She issued charters in her own name which show her granting land to the nobility and she witnessed charters issued by the bishop of Worcester. She and her husband were certainly benevolent. As well as restoring land to the community at Wenlock to keep them in food, they also intervened in a case over a monastic estate which the bishops at Worcester had been trying to recover for some years. In 909 the bones of St Oswald were translated from Bardney to Gloucester and if this was done at Æthelflæd’s behest, as seems likely then it was a shrewd move on her part. An English saint was now safe in a strong Mercia, away from overrun Viking territory. There is no doubt that her husband was ill at this point; Edward was harrying Northumbria so it might be that he brought the relics back and into her hands for safe-keeping. The minster in Gloucester dedicated to St Peter was renamed St Oswald’s, and it was here that Æthelred was buried.

|

| St Oswald's, Gloucester |

Although Æthelflæd died here in Tamworth, her body was taken back to Gloucester and she was buried at St Oswald’s, alongside her husband. She perhaps, ultimately, felt more affinity to her mother’s homeland than her father’s and despite the arranged nature and age gap of the marriage, was clearly a devoted wife, too. At some point before 911, and probably before 902, she had a daughter, Ælfwynn.

So, that’s the bare bones that we know of her life, and she clearly was a leader. She was instrumental in the repossession of the so-called Five Boroughs, and I think she must have been utterly exhausted by the time she died! But did she actually fight? And was she a queen?

If she did fight, actually wield a sword, then where did she learn the necessary skills?

I’m going to quote from Asser’s biography of Alfred, where he tells us that Æthelflæd was the first born and that ‘when the time came for her to marry, she was joined in marriage to Æthelred, ealdorman of the Mercians. Æthelgifu entered the service of God; Æthelweard, the youngest of all, was given over to training in reading and writing under the attentive care of teachers, in company with all the nobly born children of virtually the entire area and a good many of lesser birth as well. In this school, books in both languages, that is to say in Latin and English were carefully read. They also devoted themselves to writing, to such an extent that, even before they had the requisite strength for manly skills (hunting, that is, and other skills appropriate to noblemen), they were seen to be devoted and intelligent students. Edward and Ælfthryth were at all times fostered at the royal court - [and this is why some think that perhaps Æthelflæd wasn’t] - and these two have attentively learned the psalms, and books in English, and especially English poems and they very frequently make use of books.’

Now, this education seems to have been comprehensive, but it doesn’t specifically talk about the education of Æthelflæd, or say that there was any weapons training, though it does mention learning the pursuits of noblemen which we must assume means weapons training, but it doesn’t say it for Alfred’s daughters. So this isn’t especially helpful in tracking down any clues about women warriors.

We know that Edward’s own daughters were educated. An Anglo-Norman Chronicler said that Edward brought up his daughters so that, ‘in childhood they gave their whole attention to literature, and afterwards employed themselves in the labours of the distaff and the needle.’ Thus the royal daughters were literate, but also well-skilled in sewing and embroidery; excellent preparation for their adult lives as royal wives or indeed as religious women. So here we have a bit more detail but again, no mention of fighting.

Nowhere is it mentioned that royal daughters were schooled in weapons training, and it does seem rather unlikely. For details of Æthelflæd's martial activity, we can discount the ASC apart from the Mercian Register. But even that's not clear. It says she 'sent' an army into Wales, that she ‘took’ Derby, but can we confidently infer from that that she was actually leading the army? The Three Fragments says that she collected hosts and Chester was filled with her hosts, but doesn't say she was there.

|

| Psychomachia Faith conquers Idolatry – BL, Cotton Titus D. xvi, fol. 6r |

What about other written evidence? The Psychomachia is a poem by Prudentius, from the early fifth century AD and it contains images of women warriors. The trouble with this is that this work is an allegory and tells of the virtues fighting the vices, and it seems that the personifications are women because in Latin, words for abstract concepts have feminine grammatical gender. So this really isn’t much help. This is very stylised.

In the fourth volume of his Gothic Wars, Procopius of Caesarea, writing in the 550s, describes how an Anglian bride from ‘Brittia’ went on the warpath against a tribe living on the banks of the Rhine. She had been betrothed to the king of this tribe, but he had died and his successor reneged on the deal. She then took 400 ships and led the expedition personally, defeating them soundly. Now there’s a few problems with this too, because whilst Brittia could mean Britain, and perhaps even East Anglia, we don’t know for sure. We do know that the Angles living in South East ‘England’ did have strong contacts with the Continent but even if this story is true, it still took place over 400 years before Æthelflæd was born.

Now, I said at the start that Æthelflæd was almost unique in leading a kingdom. But we do have written evidence of a queen of the West Saxons whose name was Seaxburh. She was, definitely uniquely, included on a regnal list, but unlike our Æthelflæd we’re told by a later chronicler that the West Saxons would not go to war under the leadership of a woman. Bede recorded that after her husband’s death there was a troubled period during which sub-kings ‘took upon themselves the government of the kingdom, dividing it up and ruling for about ten years.’ The ASC, on the other hand, says that when her husband died she reigned one year after him. This succinct entry gives no hint about the circumstances. Was she, as would become more common, reigning on behalf of a son?

If we add to these two conflicting reports a third, that later chronicler, who said that Seaxburh ruled for one year in her husband’s stead, ‘but was expelled [from] the kingdom by the indignant nobles, who would not go to war under the conduct of a woman’, we get a scenario building where it looks like her husband died with no adult heir, and Seaxburh and the local nobility were in conflict over the succession. The chaos seems to have lasted more than a year in fact, because it’s two years before the next king is recorded. If she was fighting for her own right to the throne, and not on behalf of any sons, then she truly was a trail-blazer, but we just don’t know and I have to say that the information we have on her makes what we have on Æthelflæd seem extensive by comparison. But we just don’t know any more about her reign, just as we don’t know the circumstances that led another queen, wife of another king Wessex to (according to the ASC) raze Taunton to the ground. Kings DID fight, they led their forces. But we don’t know what the rules were for the VERY few women leaders. We must also bear in mind that these two women ruled, if that’s what they did, in the seventh century, and whilst we also know from Bede that at around the same period the Mercian king Penda left his wife in charge of Mercia for long periods while he was away fighting, he doesn’t say she fought, so it’s not enough to say that in either kingdom there was a tradition of women rulers who led armies. And, as we’ll see, Wessex did not necessarily have the same cultural identity and attitudes to royal women as Mercia.

Now, a Danish historian, Saxo Grammiticus, talked about women in Denmark dressing as men and cultivating soldiers’ skills. But Denmark isn’t England, of course, and he was also writing a good deal later - he died in around 1220.

So there’s really little in the written sources to enlighten us on this. What about the archaeological evidence then?

The obvious place to look is in graves, but of course only pre-Christian burials have grave goods. There are some where women are buried with weapons but that’s not conclusive as we don’t know the context. In 1954, two cemeteries, A and B, were excavated in Beckford, now in Hereford & Worcester, so Mercia, and Grave A2 was found to contain a female buried with a spear and shield. The skull had a lesion, maybe made by a weapon.

The report concluded that this skeleton was probably female, but the accompanying spear and shield show that it was a weapon-bearing male, and therefore more likely to incur such an injury - clearly in the 1990s the thinking was that a woman could not be a warrior, so the bone analysis must be wrong in their view. Of course, absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence but we need much more before we can say for certain that there were women warriors and we also need to remember that we have no context for this burial. It was much earlier, too, late fifth to mid sixth-century. Stating that something is true for such an early part of the Anglo-Saxon period is not automatically to say that it’s true for the later part. Remember that the Anglo-Saxon period spans the same amount of time as from present day back to the Tudors. Things changed.

So now then let's look at this notion of queenship, and a good place to start would be to go back to Asser, the monk who wrote Alfred the Great’s story and who was very much a contemporary source. He tells a very lurid tale and gives this incident as the reason why the wives of kings in Wessex were not called ‘queen’.

It concerns Eadburh, who was the daughter of Offa of Mercia, and was married to the king of the West Saxons, a man named Beorhtric. According to Asser, Eadburh resented the influence over the king of one of his chief advisors, and contrived to poison him. Sadly for her, she accidentally also poisoned the king. For punishment she was sent abroad, to the court of the emperor Charlemagne, who set her up as abbess in a nunnery. She was later found in flagrante de licto with an Englishman and died in disgrace and poverty. Henceforth, Asser says, West Saxon wives of kings were never called queen. There’s a few things amiss with this tale: firstly, the ASC records a battle in the year Beorhtric died, in which Ecgberht, Alfred’s grandfather, became king, so it’s most likely that Beorhtric met his end on that battlefield. I actually think, given that his name is much more Mercian-sounding than West Saxon, that he was a puppet king installed by Offa. If this is the case, Asser would not have wished to dwell on any reminders that Wessex was once far less powerful than Mercia and actually had a Mercian in charge of them.

And you can see how similar those coins of Offa and Charlemagne are - Offa clearly considered himself on a par with the emperor!

Now here’s a different coin and I’ll get on to that in a moment

However, whatever the reason, Æthelflæd's mother, (named Ealhswith as I said, though Asser doesn’t tell us so), was not a queen. Certainly, she didn’t witness any charters. But early on in Edward’s reign, just after Alfred died, there was a rebellion by Edward and Æthelflæd's cousin - it was a serious challenge, he declared himself to be the more throne-worthy, he minted his own coins (that's one of them above) and was eventually defeated in battle. But it is interesting to note that the rebellious cousin’s mother, was named regina in a charter whereas Edward’s and Æthelflæd's mother was not. As I said, their mother Ealhswith, never even witnessed charters. Still, Edward was declared king after Alfred’s death, not his cousin, so perhaps we should not read too much into the title of regina, and its importance in conferring status to the children of the marriage.* (Side note: Later in the tenth century it became important. King Edgar’s wife was officially crowned and a charter of 966 makes it abundantly clear that her children are throne-worthy, whereas Edgar’s older son by another woman was not (although ultimately it didn't make any difference and the older son was declared king in due course) - and it’s quite the beauty - this is the frontispiece).

[*I also mentioned that conversely, being a mother of a king brought a woman enhanced status]

We have seen that, according to Asser, the ninth-century West Saxons did not permit a king’s wife to be called queen, and actually he’s clearly wrong, because the rebellious cousin’s mother WAS called regina. An alternative title might have been hlæfdige (lady), which was used for Alfred the Great’s wife, Ealhswith. Edward had good reason to stress the status of his mother, obviously having faced rebellion so soon into his reign, and Ealhswith became the ‘true’, or ‘dear’ Lady of the English. So, the fact that her daughter Æthelflæd was called LADY of the Mercians should perhaps make us think that this was an important word, an indication of high, or even the highest status.

Edward’s second wife was evidently an important royal wife and did her duty in providing ‘an heir and a spare’. But in the only surviving charter where she appears on the witness list she is styled not regina but ‘wife of the king’ and attests after her mother-in-law, Ealhswith, (who is styled ‘mother of the king’, receiving more recognition than she had as wife of King Alfred). So I should probably just explain about these charter witness lists - they’re a record of everyone who witnessed the act that the charter records - a land grant, for example, and they go in a strict pecking order.

Now, I’ve pretty much dismissed Asser’s claims about Wessex royal wives not being called queen, and especially the reason he gave for it, but a quick look at how some notable Mercian king’s consorts were styled in charters is revealing:

Cynethryth wife of Offa - regina (she had coins minted in her name, with the title regina on them too)

Eadburh, wife of Beorhtric, even though, apparently disgraced - regina

The wife of Cenwulf, a mercian king for 25 years - regina

Æthelswith, sister of Alfred, Æthelflæd's paternal aunt - regina. [I spoke briefly about her gold ring - commissioned by her for a gift; it's too big for a woman's finger]

By contrast, in Wessex:

Wulfthryth the rebellious cousin’s mother - regina (AFTER Eadburh and the poisoning story but in Asser’s lifetime, so he’s wrong there)

But as we’ve also seen, the second wife of Edward ‘wife of the king’ [Though I mentioned that some - by no means all - historians believe that the Second Coronation Ordo was not written for Athelstan's coronation but Edward's because it includes rites for consecrating a queen]

And in that charter Ealhswith is ‘mother of the king’

So maybe there’s something going on here - Mercian royal wives, regina, regina, regina,

But with the West Saxons it’s a bit more haphazard.

Ealhswith was not to be recorded or remembered as a queen. She did not attest any charters while Alfred was alive, and we don’t know why – although Æthelflæd did. She did more than just witness them actually, as I mentioned briefly earlier and which I’ll come back to in a moment.

So we can see that some royal wives and daughters witnessed charters, including Æthelflæd, and it’s notable that part of the paradox of Æthelflæd's life is that she actually wielded much more power than all of these women who were styled regina.

We can also see that there’s no definition of a ‘queen’ per se. Sometimes this word ‘queen’ means a king’s wife, sometimes a king’s mother (and there are multiple instances of a woman’s status being elevated by being the mother of a king as we see with Ealhswith). But of course, in these terms, we then need to look at Æthelred's status, too, to determine if he was a king and if, therefore, Æthelflæd as his wife, was a queen. After all, it does seem that the wives of the kings of Mercia were indeed called regina, queen, so, if he was a king…

In the early period, royal brides brought their status with them into the marriage - for example a 7th-century king of Northumbria needed to strengthen his claim to the southern part of Northumbria, the kingdom of Deira, so chose a bride who had Deiran royal blood. Is this the case with Æthelflæd, is that what was working here with her marriage? Was Æthelred looking to enhance his status by marrying a West Saxon ‘princess’ - not that they used that word. What is unusual about the marriage is if Æthelred himself wasn’t of royal stock, this would be pretty much the first time a royal daughter had been married to a so-called commoner. It didn’t happen again until the 11th century.

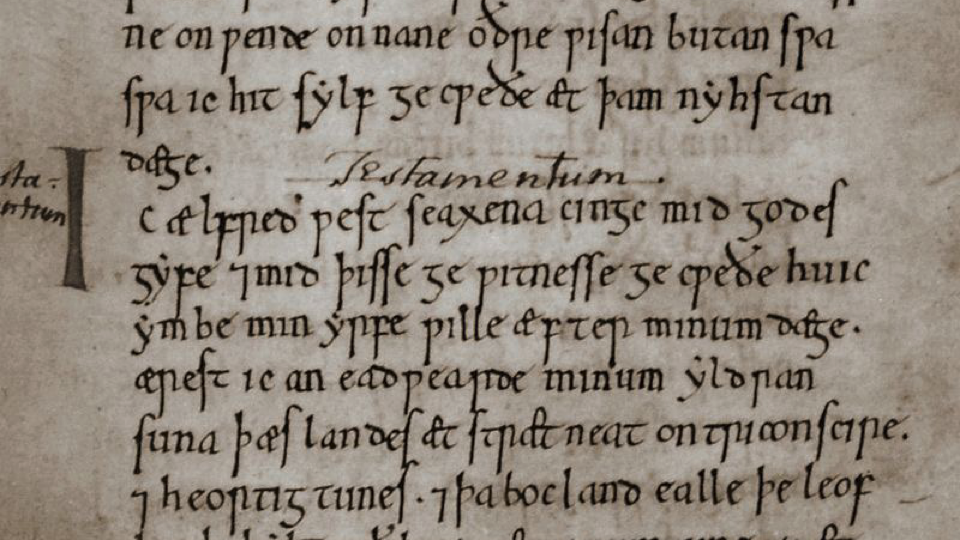

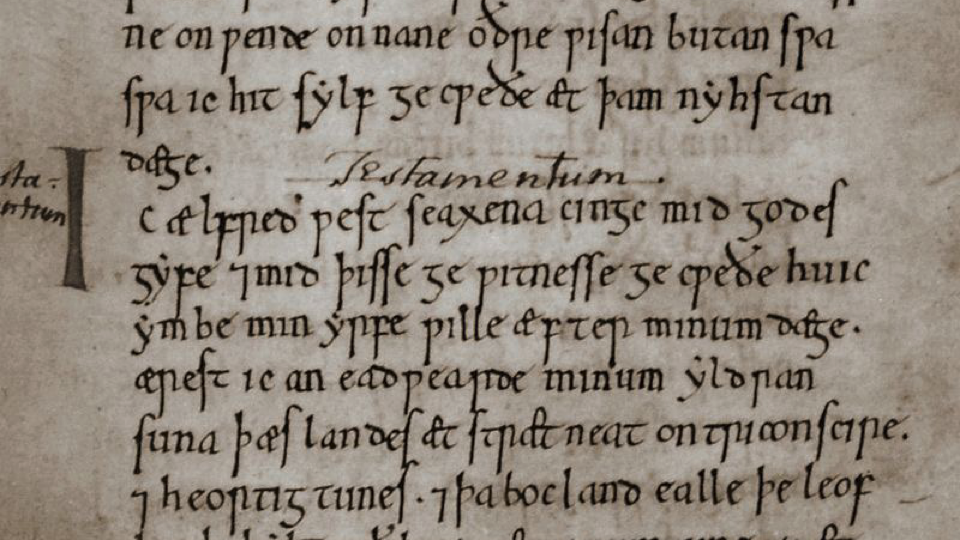

|

| Alfred's Will |

Æthelred was definitely remembered differently from the other ealdormen in Alfred’s will, being left a sword of great value. Interestingly, no mention in this will that he was Alfred’s son-in-law. Possibly because at the point at which the will was drawn up, he wasn’t, but if so, why the expensive bequest? Still, it was rare for royal daughters to marry non-royals as I said and it wouldn’t happen again until Æthelred the 'Unready' married two of his daughters to ealdormen in the early 11th century. So the evidence points to his being somewhat more than ‘just’ an ealdorman.

Now, we’ve already seen that the Irish annalists were happy to give Æthelred the title of king. They called him king of the Saxons, although actually the Mercians were more probably Angles.

The Welsh submitted to Alfred, Asser tells us, because of the ‘tyranny’ of Æthelred who was presumably acting independently of Wessex at that point.

Æthelred apparently began his reign as the ruler of an independent kingdom but there’s charter evidence which reveals that by 883 (so maybe 3 years before his marriage) he had submitted to Alfred and in that charter he’s styled (S218) ealdorman and operating with Alfred’s consent. No coins of his survive but Alfred had coins minted in Mercian towns - London, Oxford and Gloucester - which does suggest overlordship. Control of the mints is an important and significant thing. But in a way, Alfred’s forging a new kind of overlordship, one without major interference. Of course, he had other things to deal with!

Three years after his marriage, Æthelred is styled in a charter as subregulus which brings his status up a bit from ealdorman, to you know, a literal translation, subking. And it must be said that from the late 880s, after London, Alfred was styling himself Rex Anglorum Saxonus - king of the Angles AND Saxons

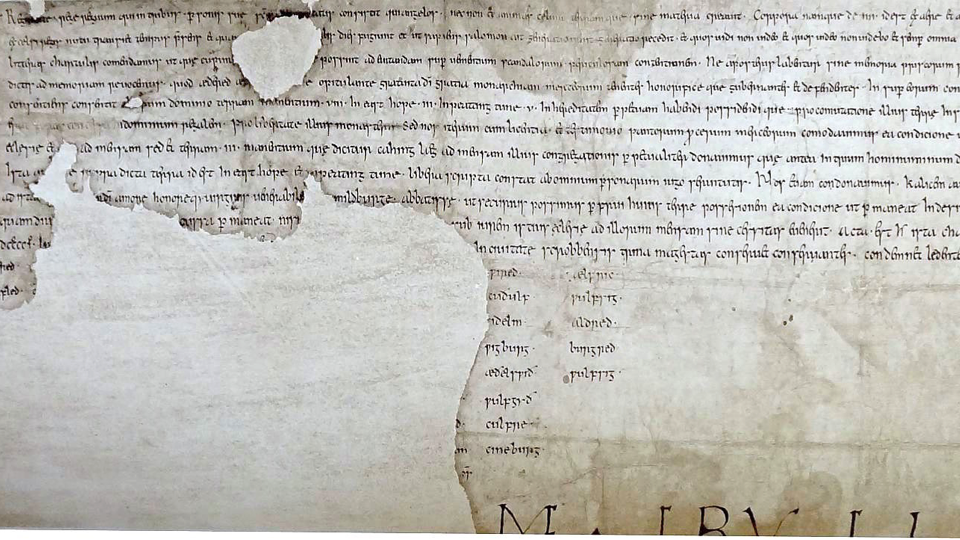

Sometimes Æthelred's granting land independently without reference to either King Alfred or King Edward, and we have the charter I mentioned earlier, where the couple give land to the religious community at Wenlock and without reference to the then king, Edward.

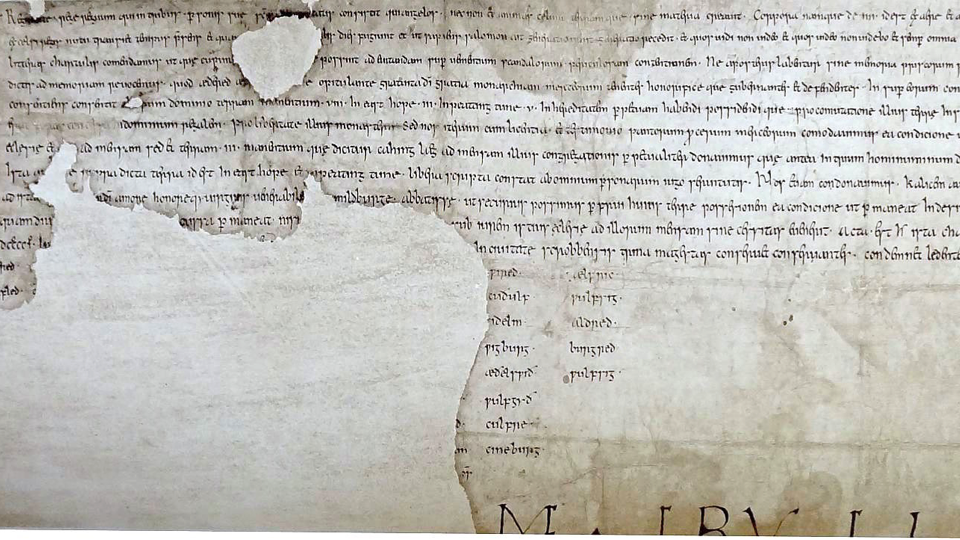

|

| Fragment of the Much Wenlock Charter |

Æthelred's an ealdorman, sometimes even a subking, in West Saxon sources, but there’s a cartulary - a collection of documents,

preserved in Worcester. It’s known as Hemming’s cartulary and among the documents is a regnal list, a king list, which includes Æthelred, so presumably at some stage the English Mercians considered him a full king.

Interestingly - another side note here: though we often speak of the Viking kingdom of York, none of the English chronicles ever name these men as being kings. So we might wonder, actually, what constitutes a king, never mind a queen!

So we’re not much further on with her husband’s status as ealdorman or king, so what about hers, independently? When Æthelred died, Edward of Wessex took over London and Oxford but was happy to leave the rest of Mercia under his sister’s direct control. Hence we can assume that there was no intrinsic aversion to female rule.

Henry of Huntingdon, an Anglo-Norman chronicler, was very taken with her, comparing her to Caesar:

Heroic Elflede! great in martial fame,�was�A queen by title, but in deeds a king.�Heroes before the Mercian heroine quail'd:�Caesar himself to win such glory fail'd.

but the contemporary records say very little about her - the main ASC doesn’t even name her. Now, it could be argued that Mercia had run out of kings, that Æthelred was a vassal of Alfred’s, and therefore the couple could not have been king and queen of Mercia.

Nevertheless, the Mercian Register makes it quite clear that in 918, Æthelflæd's daughter was deprived of all authority. Clearly the Mercians were a) happy to have not one, but two female rulers and b) considered that Edward was wrong to take Æthelflæd's daughter into Wessex, and that her authority in Mercia was absolute. Presumably they felt this way about her mother’s agency too. And let’s not ignore this point: A female ruler succeeded, albeit briefly, a female ruler. This would not happen again in English history until these two:

We can see that Æthelred and Æthelflæd issued JOINT charters, which in itself contrasts with Ealhswith who didn’t even witness any in her husband’s lifetime, but often they’re doing it with the permission of Alfred or Edward. We even then have Æthelflæd granting by herself, in Weardburh in 915 as ruler of the Mercians. But ruler, not queen. Is there a difference?

Perhaps if we move away from Wessex and Mercia things might become a little clearer - because her dealings with the Welsh and Irish Norse were different. We might wonder whether the West Saxons either thought of her as a junior partner in an alliance, or wanted history to remember her as such. The Welsh and Irish Annals clearly viewed her differently, and gave her a different title and spoke about her in different terms.

If we can believe the Irish annals, the men of York came to ask her for assistance, not her brother. Yes, Mercia is nearer, but clearly either the Irish chroniclers, and/or the men of York, were happy with the idea of a woman ruler. And the Three Fragments, remember, called her a queen who held sway.

It’s been suggested that though we know that Edward – probably in 919 – took the submission of certain Welsh rulers, they had earlier submitted to Æthelflæd, and that at her death Æthelflæd exercised some sort of hegemony over most of the major Welsh kings.

We also have to remember that the very fact that her death was recorded at all in the Welsh and Irish annals suggests that she was a leader of some significance, yet the main ASC chronicle remains very quiet about her, not even naming her as I said, just calling her Edward’s sister. The Welsh annals entry is succinct: It gives the date wrongly as 917 but it simply states that Queen Æthelflæd died.

I mentioned at the beginning the curious entry in the annals that says simply that Chester was restored in 907 i.e. taken back from Viking control. We know that Æthelred was still alive at this point but that his wife was acting on his behalf. And we know that in the Irish annals they were called king and queen. Now, the Three Fragments reads rather more like a saga than an annal, but if we look again at this idea that Chester was restored:

Chester was a significant trading centre, it was the centre of large-scale minting of coins, and merchants from all over were trading there, so it was a lucrative place to have control over.

This restoration of Chester was followed by the building of burhs along the Mersey - at Eddisbury in 914 and Runcorn in 915 (note that this is after Æthelred had died). The siting of these burhs suggests that the wary Mercian eyes were looking across the Irish sea, not to the Danes in Northumbria and the northeast of Mercia. So as well as acting in concert with her brother, she’s got one eye on the Irish Seaboard, and is effectively in control there.

So it’s perhaps in this context that we should look again at the request from York. By controlling access to Mercia from the Irish sea via the Mersey, she’s in a strong position to prevent another influx of Norse Irish, though of course they could still navigate a long way up the Ribble, north of the Mercian border. But it’s Mercia, not Wessex, that shares a border with Northumbria, and therefore with York. So to the Irish and Welsh, and indeed the Northumbrians, she’s looking powerful, not at all a junior partner of Wessex.

And although, when she died, Edward did finally take control of the whole of Mercia, Mercian history did not stop. In many ways Mercia remained independent - it seems to have welcomed Athelstan as king before the West Saxons did. Twice more in the tenth century the Mercian council opted for a different candidate from Wessex. Leading Mercians fell out with the Godwines, too, in the 11th century so there was always a strong independent/nationalist streak!

But to get back to our heroine, whom the Welsh and Irish called Queen, and who acted in every way as if she were one, more so than other women styled regina: can we answer our original questions?

Was she a warrior? It’s perhaps disappointing to some, and recent tv productions have shown otherwise, but I don’t believe Æthelflæd fought though others may choose to disagree. But I think we have to wait for more concrete evidence that there were such people in early medieval England. And I do feel that had she actually wielded a sword, someone might have commented.

It’s difficult even to know for sure if she was governing independently or whether events and decisions were engineered by the men around her (and we don’t even really know who they were). Just what advice she was getting and how much she was bound by it, we just don’t know.

She IS presented as acting independently in the Mercian Register, she and her husband are called ealdorman and lady in charters and West Saxon sources, but some Mercian, and the Irish and Welsh sources elevate them to the rank of king and queen. Whether or not she wielded a weapon, she was acting in parallel with her brother Edward. She was making decisions - again I must stress that we don’t know who, if anyone, was advising her, but it is abundantly clear that the Mercians considered her to be their rightful ruler. And her daughter after her.

What we’ll never know is why we know so little. If the West Saxons were keen to play down her role in events, was this because she was representing Mercia, or because she was a woman? If there was no intrinsic aversion to women leaders, why weren’t there more of them? Why did Edward allow her rule, but not her daughter’s - was it a matter of character? Was it a matter of timing? If she was so exceptional, why wasn’t more comment made about her at the time?

Even though she probably didn’t fight, she was a fierce and determined and undaunted person who remains pretty much unique.

Can we say that she was a queen? Well, perhaps it’s all just a question of semantics and how we define that word. The West Saxons didn’t seem to want to name her as such, but then as we’ve seen, they wanted to downplay her contribution full stop. The main version of the ASC promotes the rule of Edward, does not mention his sister by name, and incidentally even bigs up the latter part of Edward’s reign when it looks as if he was losing his grip over Mercia. Clearly Æthelflæd was acting in such a way that the Welsh and Irish thought she was a queen, and she exercised much more agency than those officially given the title. As we’ve seen, in contrast with some king’s wives who didn’t witness charters, she actually issued her own.

This woman was instrumental in stemming the tide of invading Danes, of recovering lost land, and establishing fortified towns. We’ll never know for sure whether she did that with a sword in her hand, or whether those around her called her, or thought of her as a queen, but the fact remains that when she died on June 12th 918, here in Tamworth, it ended a partnership with Wessex which had been phenomenal in fighting back the Vikings and this is how we all will remember her.

And there you can see her title: Mrycna Hlaefdige - Lady of the Mercians

The transcript of my second talk of the weekend, Prominent Women of Mercia, can be found HERE