A family featuring prominently in my writing, both fiction and nonfiction, is that of seventh-century Merewalh of the Magonsæte, all of whom had names beginning with M, which perhaps displays either a lack of imagination, or a strong sense of kin!

The alliterative nature of the names is interesting, as it has often been cited as a reason to dismiss the idea that Merewalh was a son of Penda, the seventh-century pagan king of Mercia. But of Penda's numerous children only one, in fact, had a name beginning with P, so this is not a strong enough reason to say that Merewalh was not one of Penda's sons. The last part of his name causes more debate, because it suggests to some that he was either a slave (Old English wealh) or, perhaps more probably, a Welshman. Penda had strong friendships and alliances with the British living in what we now call Wales, and there was also likely to have been a lot of intermarriage between Mercians and 'Welsh'. There were kings/subkings/noblemen with this name element - Cenwalh, Æthelwalh, and Penwalh, for example - and I don't think it should tax us unduly, other than to note that it, along with others, might indicate a degree of intermarriage. Merewalh, it is assumed, was given the rule of the area where the people known as the Magonsætan by Penda, so perhaps it was either because he was Penda's son, or foster son, or because he was a Welsh ally rewarded for help/service.

|

| Penda of Mercia |

The Magonsæte was a subkingdom of Mercia, centred around Hereford, though the name itself is not recorded earlier than 811 and it may have been home to a culturally and ethnically diverse population. Merewalh, despite having at least three sons, didn't establish a ruling dynasty, and the area was later absorbed into greater Mercia.

It seems that Merewalh was married twice, and his first marriage produced sons Merchelm and Mildfrith. His second marriage resulted in yet more little Ms: daughters Mildburg, Mildthryth and Mildgyth, along with another son, Merefin, who did not survive infancy.

We have very little information about Merewalh's sons; however, material does survive which tells us about his daughters. But first, mention must be made of his second wife who, you'll be pleased to hear, did not have a name beginning with M, though her name has caused plenty of confusion! She is sometimes mistakenly called Eormenburg, has been sometimes called Æbbe, but she was actually Eafe, or Domne Eafe (Domneva), daughter of a Kentish king.

Domne Eafe had two brothers who were killed by their cousin. A famous story concerns how she demanded compensation from their killer, and duped him into giving her more land than he'd anticipated. On this land she founded an abbey, Minster-in-Thanet, and it is still home to a community of nuns to this day, and part of the original building survives.

|

| Minster Abbey, showing Saxon stonework (photo by kind permission of the community there) |

Of her daughters, Mildgyth remains a shadowy figure, about whom we have no information beyond that she was buried somewhere in Northumbria; some have questioned whether she even existed.

We are on surer ground with the other two daughters. Mildrith, we are told, was sent abroad, to receive her education at the monastery at Chelles, in Frankia. The abbess attempted to force her into marriage with one of her kinsmen and, when Mildrith refused to acquiesce, she was put in a hot oven, but miraculously managed to escape. The abbess then beat her so viciously that her hair was torn out. Mildrith sent some of this hair to her mother as an SOS signal. Domne Eafe sent a rescue party, although Mildrith refused to leave until she had collected some holy relics from her room. The delay meant that they were pursued and were only successful in escaping because the tide turned. No doubt her mother was pleased to see her again; Mildrith entered Domne Eafe’s house at Minster-in-Thanet and eventually succeeded her as abbess.

|

| Tapestry owned by Minster Abbey, depicting the first three abbesses, including Domneva and Mildrith |

The remaining sister, Mildburg, became the second abbess of Wenlock, and many miracles were associated with her.

An important document, the Testament of St Mildburg, speaks of land and gifts granted to her by her brothers, Merchelm and Mildfrith, although the language used suggests that they were her half-siblings (thus the assertion above that Merewalh married twice). In the Testament, Merchelm is styled rex but if he did, indeed, succeed his father as king of the Magonsæte the line stopped with him. Mildfrith was named regulus in a monumental inscription set up by Cuthbert, bishop of Hereford in the eighth century. Perhaps the brothers ruled jointly? The only other information we have of Mildfrith is a story concerning the murder of Æthelberht of East Anglia by Offa, king of Mercia. Apparently, upon hearing reports of miracles associated with the victim, Mildfrith founded a minster at Hereford. But Mildfrith must have been long dead by the time of this murder, which occurred in 794.The Testament does tell us though that his sister, or half-sister Mildburg, was still alive in 727, and possibly even in 736.

|

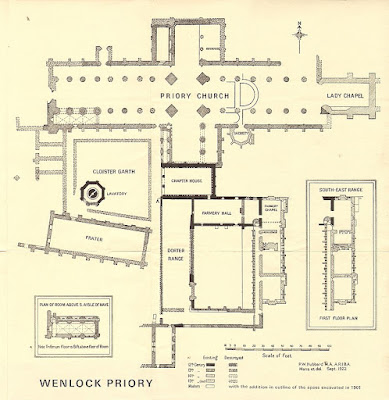

| Plan of the later medieval buildings at Wenlock |

Before she became abbess at Wenlock it had been under the auspices of the abbot of an East Anglian abbey and an abbess who came there from Chelles. As already mentioned, we know that Mildrith was educated at Chelles, and it is possible that Mildburg also spent some time there. A curious mix, then, produced a religious house in Mercia, on the Welsh border, founded initially by East Anglians and styled on Frankish models.

It seems that Mildburg also had connections with Llanfillo, near Brecon; during the seventh century relations between the Mercians and the Welsh had been good – her grandfather Penda and Cadwallon of Gwynedd had fought as allies against the Northumbrians – so perhaps there is a possibility that Mildburg’s father Merewalh was indeed a Welshman, given land for service by Penda, or that perhaps he was Penda’s Welsh son-in-law, by dint of his first marriage, rather than his son.

The name Magonsætan was mentioned as late at 1041, so it seems that some 'tribal' memory/identity remained centuries later.

You can read more about Merewalh and his family in my nonfiction books, Mercia: The Rise and Fall of a Kingdom and Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England. They also appear in my novel about Penda, Cometh the Hour, and feature prominently in the follow-up, The Sins of the Father.

I've revisited the murder of Domneva's brothers in my new book, Murder in Anglo-Saxon England: Justice, Wergild, Revenge